Why The Conventional Training Sessions Aren't Working

Coaches have the crucial role to improve motor and cognitive learning in our athletes to improve sports performance, so it’s paramount that we understand the methods of practice that we use.

It is widely assumed that practising a skill or task over and over again will result in better performance and an improvement in long term learning, cognitive or motor. You see it all over from schools to sports teams worldwide, people practising a skill over and over.

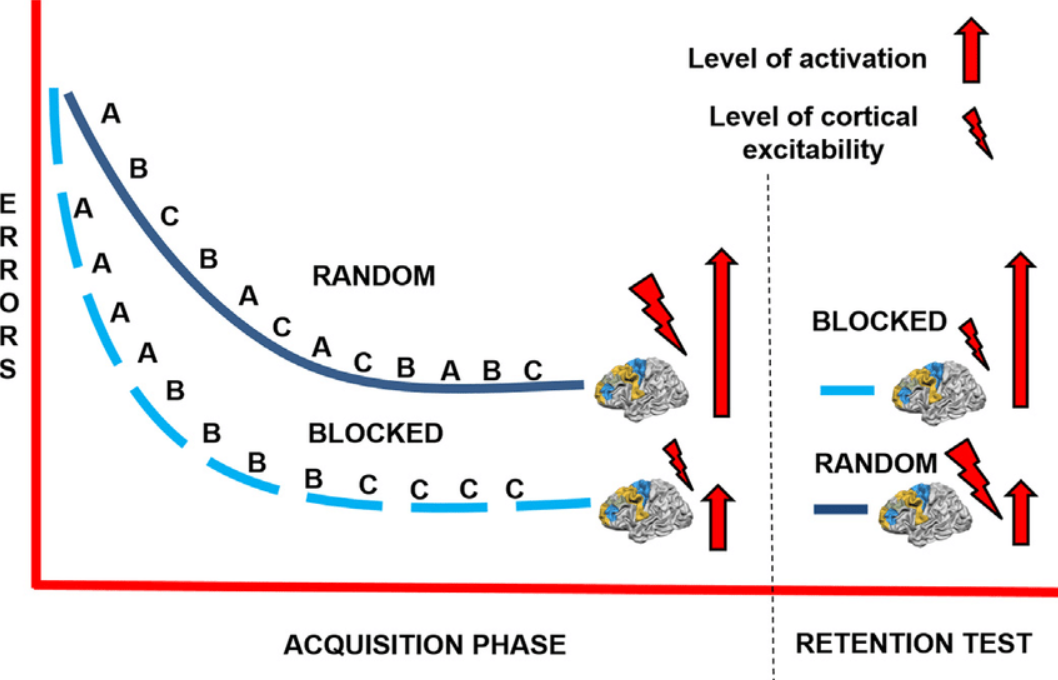

Random vs. blocked practice and corresponding levels of cortical activation and excitability. Random practice showed poorer performance during skill acquisition. However, physiological processes occur in key cortical areas for learning, favouring the retention of the practiced skills (Lage et al, 2015).

Blocked practice is the ‘one thing at a time’ method of learning. A classic example of this is in basketball, shooting X number of 3 pointers at the end of the training session, often as high as 100+. This intense and condensed period of practising one skill often leads to rapid improvements in performance, as we would expect. High focus on one area or skill also gives us the feeling that we are improving. The problem is, we are terrible at accurately gauging how much we are improving and learning.

Blocked practice may be useful to gain short term improvements, however during retention tests after a certain period of time, the gains made are quickly forgotten or diminished. Why? Because they are practised in an environment that isn’t real. Let’s go back to our Basketball example, in no game situation ever, are players allowed to just stand there and shoot 3 pointers. It’s just not part of the game. There is minimal transfer, they simply get better at 3 pointers but can’t apply it when the environment is realistic.

Enter varied practice.

This is the opposite of blocked practice. Variable practice is when multiple tasks being learnt at the same time are mixed up, or interleaved, with each other. This means less time is spent learning each task, learning is slower, and often the learning is frustrating with people feeling they aren’t learning as much as compared to blocked practice. Sounds counterproductive, we know.

However, this method of learning often has the greatest effect on long-term learning. This is due to the Contextual Interference effect. The contextual inference is a learning benefit that is lower in blocked practice as there is less disruption, or interference, on the learner’s memory and attention due to the repeated attempts at the skill repeating over and over. Sounds great, right? Well, not always. This almost robotic attempt at learning employs what is known as passive learning, where the learners attention and focus is minimal. The sheer repetition causes a temporary increase in performance, which is then lost in later retention tests. Varied practice employs active learning, by switching between different, sometimes completely unrelated, subjects or skills the learner cannot switch off. In short, contextual interference boosts learning by keeping the learning engaged and active in the process and allows skills to be learned in a more realistic environment that allows for greater skill transfer and long-term learning.

So which is best, blocked or varied? Well, as always… neither. Each has its place in motor and cognitive learning. Blocked practice is likely best during complex tasks that require high repetition or in cases where the athlete could benefit from focusing on one skill to boost motivation. Varied practice could be used to gain higher understanding, learning and transfer of skills to the context to which they need to be applied.