Shoulder Anatomy

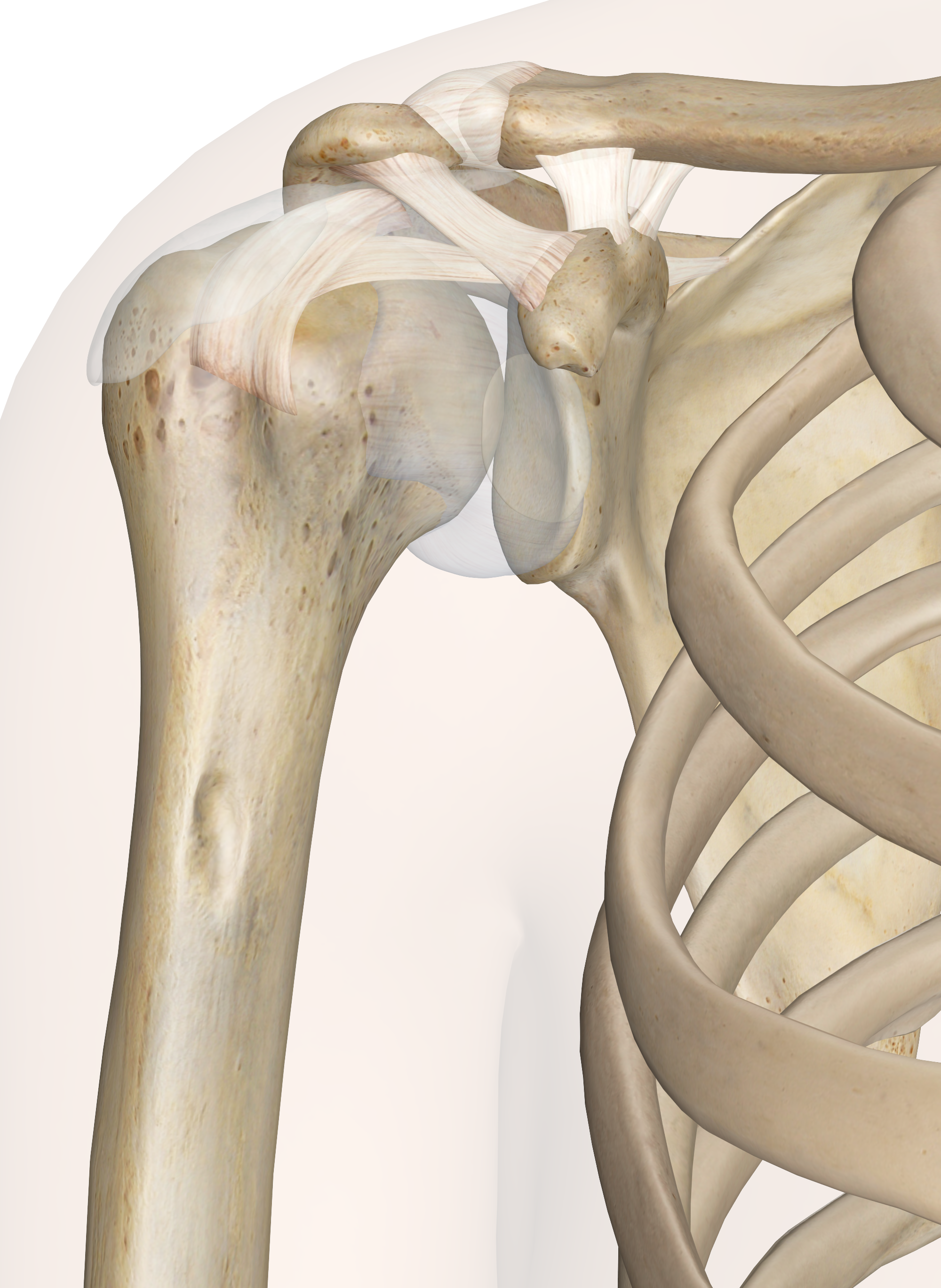

Shoulder (Glenohumeral) Joint. Note the depth of the Glenoid Cavity.

Swimmers must have strong, mobility and stable shoulders if they are to succeed and live a life without constant pain. Recently 5x gold medalist Missy Franklin retired from swimming at 23, this is such an early age for a world-class athlete, the reason… shoulder pain. Part of the philosophy at Velocity Swimming isn’t just about athletes during their career, it’s about looking after them now, so they don’t have such issues when they are 40+ with a family.

The retirement of Missy highlights the need for education in swimming programmes across the country and world in basic shoulder anatomy to protect athletes from intense unnatural loading of the shoulder. Clearly, the evolution of humans made the legs and hips the main weight-bearing parts of the skeleton, the shoulders never evolved to cope with the demands of swimming… we moved out of the ocean millions of years ago, hence why shoulder related injuries are so common.

The shoulder is a ‘Ball and Socket’ joint, but it’s more like a ‘Golf Ball and Tee’ joint. The head of the Humerus is the golf ball, and the Glenoid Cavity is the tee. The Glenoid cavity is extremely shallow, it barely has any depth at all and thus further tissue is present to increase the depth called the Glenoid Labrum. This tissue tops the edge of the Glenoid Cavity to increase the depth and passive stability, being stability without active input from the person. Unlike the hip, there is no ligament securing the Humeral Head to the Glenoid Cavity, so the remaining passive stability is the Capsule, a double-layered circular ligament encompassing the Humeral Head and Glenoid Cavity. The inner layer produces the famous Synovial Fluid, the oil in the engine, to lubricate the Glenohumeral Joint. The second, or outer, layer further assists in stabilising the joint.

Next up is active stability, the infamous Rotate Cuff. This is 4 individual muscles groups that help to secure the Humeral Head into the Glenoid Cavity. It’s easy to think these muscles simply rotate the arm, that is their secondary function, secondary. First and foremost, each muscle group is positioned to pull the Humeral Head back into position, centred in the Glenoid Cavity. A loss of function or injury to one of these muscle groups can cause added load on passive tissues such as the Capsule or Labrum and create joint instability.

Land-based training must be in place to correctly increase the stability of the shoulder. Shoulder stability can be stroke-specific, for example, backstroke athletes can have instability in the anterior (front) shoulder capsule causing the Humeral Head to move forwards in the Glenoid Cavity creating further problems such as impingement, pain and tendinopathies.

Careful programming for both pool and land-based training must be implemented so as not to overload the shoulder too much and allow for strength adaptation and recovery.